In a prior blog post, I spoke to the common challenges faced by correctional leaders on their journey to a more restorative approach to corrections. I highlighted the immense impact staff culture has on the success of these efforts, and nowhere is that more apparent than in our implementation of effective, impactful staff training. In this post, I dive deeper into the subject of training and show why sometimes the best path forward is a return to the basics.

In corrections, we are quite good at managing emergencies. Virtually every day, in every prison, staff manage situations that threaten the safety of staff and inmates and security of the institution and community.

Unfortunately, such incidents are normally viewed as idiosyncratic events which do not appear to have any connection, one to the other. The incident is reviewed, discipline may be imposed, staff and/or inmate policies are revised, procedures updated, or other actions are taken. Often, if the incident is serious, there is an expectation that “heads roll” and the Warden finds him/herself in jeopardy of his/her job. However, upon careful examination, a common thread can often be found in incidents occurring over time in several different institutions.

The Role of Staff Negligence and Lack of Training

A nationwide review of after-action reports of escapes, staff assaults, hostage situations, disturbances or other serious problems reveals few instances in which malfunctioning locks or electronic detection systems, insufficient razor wire or other deficiencies in physical plant or technology were responsible. Rather, most serious security breaches occurred because one or more staff members took a “shortcut,” did not know what was expected of them or simply failed to follow established security procedures. Though weaknesses in the physical plant may have contributed to the problem, it was usually the failure of staff to attend to business that was at the heart of the incident.

In other words – “people-system failures,” not “physical-system failures” account for most security breakdowns.

An example of such an incident is the widely known escape of five high-risk inmates from a privately operated facility in Ohio in 2020. Upon examination, it was found that, first, the inmates were inappropriately classified and should not have been housed in this medium security prison. Second, after a soccer ball struck the fence several times, activating the alarm each time, the alarm was disregarded. Third, an employee with a personal relationship with an inmate was believed to have brought wire cutters into the institution – if not, there was a breakdown in the tool control operation. If any one of these separate and distinct performance failures had not occurred, the incident could not have occurred.

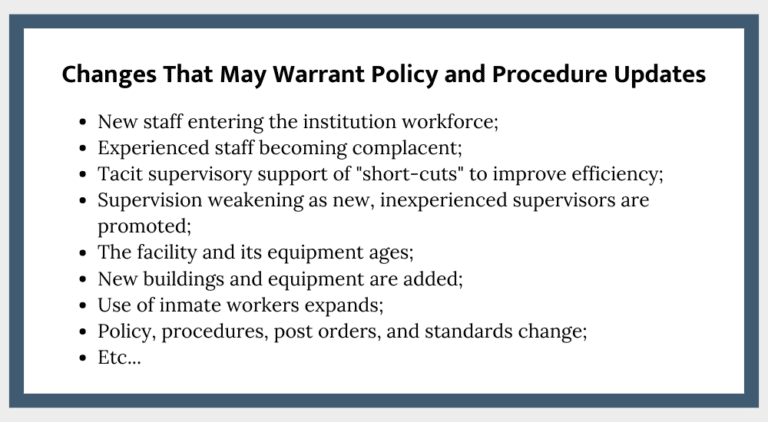

The most common response when serious incidents occur is to “fix the blame” and identify someone to discipline rather than “fix the problem.” More often than not, the problem is both a performance problem and a failure to train and supervise. Managers are often slow to recognize “slippage” in security practices or the need for policy and procedure upgrades as changes occur. Such changes may include:

- new staff entering the institution workforce;

- experienced staff becoming complacent;

- tacit supervisory support of “short-cuts” to improve efficiency;

- supervision weakening as new, inexperienced supervisors are promoted;

- the facility and its equipment ages;

- new buildings and equipment are added;

- use of inmate workers expands;

- policy, procedures, post orders, and standards change;

- etc…

This phenomenon, the failure of staff to reliably carry out all of the duties and responsibilities of their jobs, all of the time, underscores the importance and value of a back-to-basics emphasis in training.

Back-to-Basics In-Service Training

While there are many ways of getting back-to-basics, the approach discussed here is in the context of an in-service program in which staff of multiple disciplines within the institution are brought together for training.

Activity 1: Setting the Foundation – Understanding Liability and Emphasizing Fundamentals

As an introduction to the training, the leader (Warden?) should discuss the activities of the training (in very general terms), as to prepare the staff and underline the significance and motivation behind the effort.

Early in the discussion of the Back-to-Basics training, it is important that the Warden discuss liability with the group. It is imperative that amnesty is

given upfront for any policy or other violation acknowledged by the officer or brought to light by other staff. The objective is honest, complete responses to key questions and other inquiries. Understanding that problems of performance are often both a performance problem and a failure to train and supervise, no one will be singled out for discipline or chastisement.

Following the Warden’s discussion, group discussion may be promoted through the use of questions which may include:

- What has changed in our institution that may make it important for us to go Back-to-Basics?

- In what ways have these changes hampered good security?

- In what ways, if any, have we gotten away from attention to the basic fundamentals in security operations?

- Who is responsible for security? Is security a “program” or a “culture?” What does “seamless” security mean?

Activity 2: Preparing for the Worst – Small Group Discussions on Potential Incidents in the Prison

It is recommended that the group now be divided into small groups of 8 – 10 staff and that each group select a group leader. Each group is charged to address the following question:

The group should be appraised of the following “ground rules:”

- Each group member is to respond.

- There is no “right” or “wrong” answer. It is imperative that all group members feel free to contribute openly and honestly. Members may ask for clarification but there is to be NO disputing or arguing a member’s contribution.

- All responses are to be listed in full.

When the groups have completed their work, they will report their observations to the large group. The Warden and administrative staff should be present for this report. A full-group discussion of the responses may now take place as the administrative staff attempt to fully understand the nature and scope of the concerns that have been elicited from the group members.

Activity 3: Analyzing Concerns Raised – Identifying Immediate Response Needs and Learning Opportunities

The Warden and administrative staff should review the concerns elicited from the group members apart from the group. An assessment should be made of each of them, determining if there is information of a nature that dictates an immediate response to prevent the incident. The second level of assessment should be to select post-related concerns that can be further examined by the in-service training groups as a learning activity. For example, if a group member suggests that, within the next six months, an inmate is going to exit the rear sally port in a garbage vehicle, the posts responsible for this activity could be identified as a post for examination by a training group.

Activity 4: Preparing for Effective Post Management: Essential Components of a Post Packet

After identifying post-related concerns, a packet should be prepared for the group examining the post. It should include policy and procedure, post orders, standards and regulations, schedules, and other information pertaining to post activity and the responsibility of the assigned staff.

Activity 5: Analyzing Post Operations – A Collaborative Approach

As the training group reconvenes, they are divided into groups and each group should be commissioned to study and examine the operation of the post, including the policy, procedure, post orders, etc. that are included in the packet. These documents should be reviewed for clarity, comprehensiveness, consistency between documents, etc. The group should then discuss the operation with the responsible staff, eliciting concerns and suggestions from them regarding the operation of the post. They will observe the operation for several hours during which time the concerns about the post brought forth in the earlier group meeting will be a focus.

Upon completion of their examination, the group should meet and prepare a report for the administrative staff. The report should include a review of their activities, a record of their observations regarding the documented responsibilities of the post as compared to the operation of the post, and their recommendations.

Activity 6: Maximizing the Value of In-Service Training: Inclusive Feedback and Partnership with Post Examiners

Following a full review of the recommendations, the administrative staff should determine what changes, if any, will be made in the specific posts or operations and that feedback should be given to the group. Insofar as is possible, feedback should be face-to-face and to all staff who reviewed the post under consideration. Staff assigned to the post should, ideally, be included in the meeting and, if not, immediately informed of the outcome of the examination and the administrative staff’s decisions.

The group should be informed of the way in which the concern is being addressed. If recommendations are not accepted, the group should be told why or what is being done instead of the recommended action.

The back-to-basics training should be more than an exercise and should demonstrate the belief that security IS everyone’s business, and that staff observations and recommendations are important and valid.

Much of the value of the back-to-basics in-service training, as in any training, can be lost in the administrative response or lack thereof. As is the case with any attempt to improve organizational culture, failure to be inclusive, give feedback, give reasons, and give credit can quickly undermine the program. With each effort in which post examiners are not included as full partners, the meaning and value decreases – staff will feel that they are being “used” or the training will become perceived as a meaningless exercise.

Conclusion:

“Security is everyone’s business” is a well-worn banner. Yet, we bear labels such as “security staff” and “civilians” or “non-security staff.” We have the mystique of key control, emergency response, etc., the secrets of which we dare not share with “non-security” staff. And, we have the “Security Department” and “Programs Department” and myriad other terms and titles that belie our “everyone’s business” banner.

An effective security program is a program without seams. All institution operations and activities are inter-connected in a seamless system in which all parts “talk” to each other in ways that prevent inmates, inmate needs and concerns, programs, security, operations, or administrative concerns from “falling through the cracks.”

Think about it. An effective security or treatment program is not a “program”; if it is truly effective it has become the culture of the organization. Until it becomes the culture of the organization, it cannot be truly effective. We would not say of our safety concerns for our children that we have a “security program” to ensure their safety – safety and security is a culture in our homes that pervades every consideration and every activity.

This back-to-basics in-service training has great potential to revolutionize our approach to security operations. It is “one small step” in sharing – acknowledging that staff at every level in all parts of the institution have interest and concerns about safety and security. And it is a “giant step” toward inclusion – including those who have been “on the outside, looking in” in the responsibility for safety and security and enlisting their help in making critical decisions that affect the life of the institution and its residents.