When it comes to planning for a new criminal justice project, it’s important to consider all the elements at stake in order to determine, “Is this project really feasible?” Feasibility studies do just that, and that’s why they’re a vital tool in any justice planner’s toolkit. We sat down with Brett Firfer, an expert in the field with more than 24 years of experience doing feasibility studies. In this post, Brett shares his insights on what feasibility studies are, how they work, and why they’re so crucial to the success of any criminal justice project.

Download the Case Study (PDF)Let’s start with the fundamentals…What is a ‘feasibility study’?

Simply put, a feasibility study is an objective analysis meant to ascertain whether a project is meeting a certain set of criteria, requirements, goals…basically, addressing the question, “Is there a project or a change that could happen that makes sense?”

Why might a client need a feasibility study?

Could be quite a number of reasons. Sometimes there’s overcrowding in an active building and there’s a feeling like more space is needed. It could be the aging infrastructure is no longer appropriate for an operation or building maintenance costs are escalating at an alarming rate. Maybe there just happens to be an opportunity to do a project because a desirable property becomes available or maybe a major storm or some other emergency has unexpectedly created a need to replace or upgrade infrastructure. Of course, sometimes it’s just politics – an elected official or a judge wants a new building or wants to move operations to a different location. Before moving forward, it makes sense to have someone come in and take an objective look at the pros and cons of making a profound change or spending significant public money before committing to moving forward.

Why are feasibility studies important for criminal justice planning and the criminal justice community in general?

There’s a social and civic responsibility to spend public money effectively. That’s a key reason why doing these feasibility analyses are important to make sure that it’s not “ready, fire, aim.” Projects – including operational analyses, not just capital projects – are going to have profound impacts on the lives of the participants in the justice system.

So doing this well means that on the courts side, it’s the judge, it’s the litigants, it’s the defendants, it’s families that are affected. And on the corrections or detention side, we’ve got people who are in custody who are very much impacted because they live in these facilities. But it’s also the staff who come day-in and day-out who need to have a positive work environment to come to.

And it’s important for for recruitment and retention. Taking the time to do a feasibility study to really think through, “What is the right project?” and “What is the right thing to have for any particular participant?” is really important. Fundamentally, we need to make sure that we’re thinking about that and asking, “Can we do this project? If not, what are our alternatives?”

Who’s typically involved in a feasibility study?

People who are typically involved in a feasibility study would be anyone who would have a strong understanding of the goals of the study. There should be an expert on the issues related to what’s being studied and analyzed and be able to take an objective and impartial view of the findings. I think that last point, ‘needing to be objective’, is why a feasibility study typically should be undertaken by an outside party – it’s the best way to ensure that findings are as unbiased as possible.

On the client side, you want to make sure that policymakers – people who actually have the ability to make a decision – are involved. It’s one thing to have somebody be involved in the study because they are very much entrenched – and you definitely need those internal experts involved – but at some point, policymakers also need to get involved to make sure that whatever happens is actionable.

What types of information can a feasibility study reveal?

While most of our clients typically have a project in mind when we have engaged in the study – and they might even have an answer that they really just want us to validate for them – but I’d say a well done study will usually reveal surprising insights into their business as usual. Insights that suggests a system might find improvements just by trying new things occasionally before a capital project needs to be done. It doesn’t mean that a project isn’t still the best option on the table, but it does mean that the mere effort of engaging real experts with broader experience outside of the provincial system could help usher in unexpected benefits, especially for open-minded clients.

Walk us through the typical process of conducting a feasibility analysis with a client. What does the process entail?

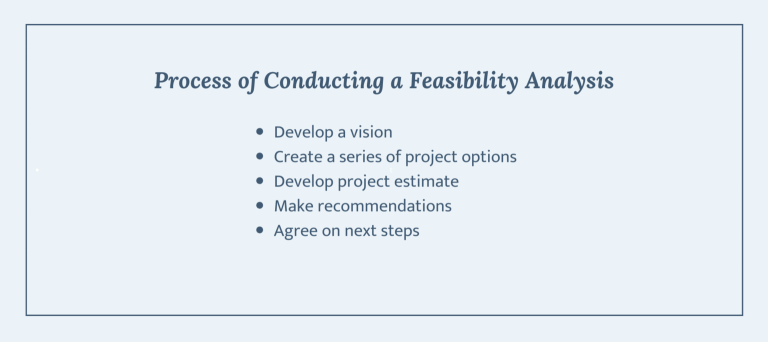

For a feasibility analysis, the first good step is to develop a vision. Whether through a workshop or just some open conversations with key stakeholders, developing consensus among those key stakeholders paves the way to an outcome that will ultimately be widely accepted. It also sets the process on a path that’s clear to everyone and usually adds some transparency to the process.

So then, in separate tracks, there should be an assessment of existing conditions and a process to determine current and projected needs. The scale of each – how detailed, how high level the effort – should be appropriate to the goals that are trying to be achieved. Therefore these tasks are going to provide a sense of how far apart the needs are from what is existing, “What is that delta that needs to be bridged?” Then, once we’re armed with this information, the next step is project options – or a series of project options – that would be developed and evaluated against the goals and objectives that were hopefully established in that initial vision.

Typically, a cost estimate is going to be included as part of this exercise and that will also be important information for determining whether a project is a good value project, whether it meets all the goals, the objectives, including fitting within a budget. Finally, after that, our recommendations are made. At that point, hopefully a decision is reached about moving forward with the project or not. Lastly, there would be agreed-upon next steps on how to follow through on the findings and recommendations from the feasibility analysis.

How long does the process of a feasibility analysis typically take?

It really depends on the scale of the project and what the goals are. For example, New York City has been trying to replace Rikers Island, which is obviously going to take years. We spent a good couple of years just developing options and a path forward that the city would then go ahead and turn into projects that they would bid out. For projects of a smaller scale, sometimes it’s just a matter of looking at a building, walking around and measuring the square footage and saying, “Okay, this is what the difference is,” and in those cases, it could take a matter of weeks.

What are some challenges criminal justice agencies might encounter when conducting a feasibility study?

I’m going to identify a pet peeve of mine on these projects….

Once I hear a few sentences that begin with the words, “Well, the way we do things now…” I know someone is struggling to move forward. It’s okay to have a baseline in context to work from, but the baseline of one’s current way of doing things should not be a touchstone for moving forward.

I want to see a mission statement or a list of goals and objectives – the vision that should be the touchstone. I’d say the biggest challenge so many of our clients struggle with is getting out of their current box; envisioning something new and knowing that what they have, the way they do things now, is very much a product of the infrastructure that they’re working with and the operational organization that they inherited from their predecessors. Doing something new, doing a new project – whether it’s a new building, reimagining their existing space, or maybe reassigning staff and doing things differently – is an opportunity to not just update the brick and mortar element of what they have, but it’s also an opportunity to rethink how they do things.

That’s probably the biggest challenge that we see. Other challenges are going to be the political issues. Sometimes there is a political force at play that is pushing a project or an idea in a certain direction, and it might put pressure on our process to try to tilt the feasibility study in a way that isn’t objective. We have to make sure that we maintain our integrity as we go forward and let our recommendations be what they are.

What are some ways to ensure that the outcomes of a feasibility study are actionable and measurable? How do we measure the success of a feasibility study?

If we want to make sure that the outcome is going to be actionable and that the outcomes can be achieved, it really does begin with that visioning at the beginning.

If we can envision what the goals are, what the objectives are, where we want this potential project or change to lead to, then we have something to measure against. Once we have something to measure against, we have consensus. Then, when we start measuring our options against the vision from the beginning, it’s inevitably going to be more supported.

How do we measure that we got to the finish line in a way that worked? In the end, only the client can really determine whether or not this effort was successful by what they do with the findings. If they take the study and put it on a shelf, they’re making a de facto decision not to do anything. If they, with intention, say, “We’re not doing anything,” but they still have that as part of their data for going forward, and maybe in a year or two, they look at another study – even that’s something. If they take a feasibility study and actually pick something and move forward with it, that’s a way to know that there is some success – that they could act on what we did. In the end, we’re just helping our clients be empowered to make a final decision, but they have to be the ones to make that final decision.

Any advice you want to share with clients who are considering a feasibility study?

Make sure that you have a good team internally. Engage when you have the right people that understand what the issues are and are motivated to do something positive – that already puts you in the right place. Also don’t leave key stakeholders without an invitation to the table. That’s going to help make sure that before you’ve even taken that first step, the people who might give you the most potential obstacles along the way are already being included and feel like they’re on the team.

Lastly, make sure that you have a pretty good idea where you want to go with this project. If someone brings in a consultant and has a very muddled scope, it’s going to make for a lot more time spent on a study just trying to define what the study should look like. If you already know from the outset, “this is the issue we’re trying to address,” and we already have some potential ideas about what might be possible, that helps us get started. We’ll find other potential options out there, but if we’re starting without any preliminary ideas from a client who might not be prepared to even start a visioing session, it will add time and time is more fee money in the process.