The Problem

Anyone associated with the world of design and construction knows that construction prices have been extremely volatile in recent years – it’s no secret. In fact, there are countless data sources that illustrate this volatility.

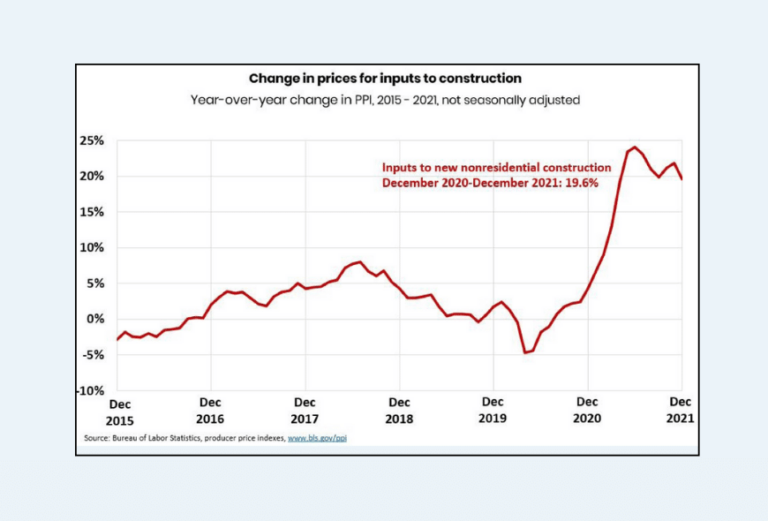

Changes in prices for inputs to construction. Image credit: The Associated General Contractors of America (AGC) 2022 Construction Inflation Alert; Data source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, for the period December 2015 to December 2020, the year-over-year change in inputs to new non-residential construction varied from approximately -5% to approximately + 8%. In December 2021, the year-over-year change was 19.6%. This volatility in inputs had a direct impact on the prices seen by owners of construction projects.

How Did We Get Here?

By now, the sources of this volatility are well documented: Covid, supply chain disruptions, workforce shortages, foreign wars, domestic energy policy, and other factors have resulted in an extremely volatile construction economy. This, in turn, has made the task of establishing budgets for capital projects – new construction and renovation projects alike – more challenging than ever. This is simply the reality that we live in. And while this challenge is no surprise to those involved in design and construction, it still begs the question, “where do we go from here?”

9 Budgeting Best Practices to Navigate an Extremely Volatile Construction Economy

The purpose of this blog post is not to dissect the causes of past and current volatility, nor is it to predict what will happen in the future. Instead, the purpose is to equip Owners and Owner Representatives with best practices they can employ to help establish project budgets in an extremely volatile construction economy.

Best Practice #1: Capital Project Budgeting Should Be an Extension of a Master Planning Effort

In a recent CGL blog post on Master Planning, we made the point that it is always recommended to include in the Master Planning effort the people who will execute the plan. Establishing a project or program budget is one step in executing an overall plan. As with any project, cost is tied directly to scope. In times of construction market volatility, having a thorough understanding of the overall plan – i.e., the Master Plan – will enable budgeters and decision makers to understand which scope elements are needed immediately, which elements may be deferred for some period of time, and which scope elements could be deferred indefinitely. This ability to strategically prioritize needs will prove invaluable to the budgeting process.

Best Practice #2: Avoid Speaking in Absolutes

Budgeting for a capital project normally occurs early in the project or program delivery cycle – typically before design even begins. At these early stages, it is vital to speak in general terms. An unfortunate reality is that the first number spoken is usually the only one people will remember. With this in mind, we should never say: “The project will cost $X.”

Instead, the more effective way to talk about project budgets, particularly in the early stages, is to say something along the lines of: “We expect the project to cost approximately between $X and $Y, but this is only a projection, which is based on a number of assumptions. If those assumptions don’t prove true, the actual project costs could differ, even significantly.”

Best Practice #3: Communicate Consistently

Capital project budgeting is rarely an immediate event executed by a small group of people. Instead, the process normally involves a large number of people working over extended periods of time – months or in some cases, years. It is therefore critical to be consistent in how project budgets are discussed and communicated.

Some prefer to talk in terms of cost per square foot. Others prefer cost per bed. Still others prefer to speak only in overall project costs. Regardless of how the projected costs are communicated, it is important to be consistent. In times of pricing volatility, the numbers will inevitably change – the words we use shouldn’t.

Best Practice #4: Think and Communicate in Terms of Total Project Costs

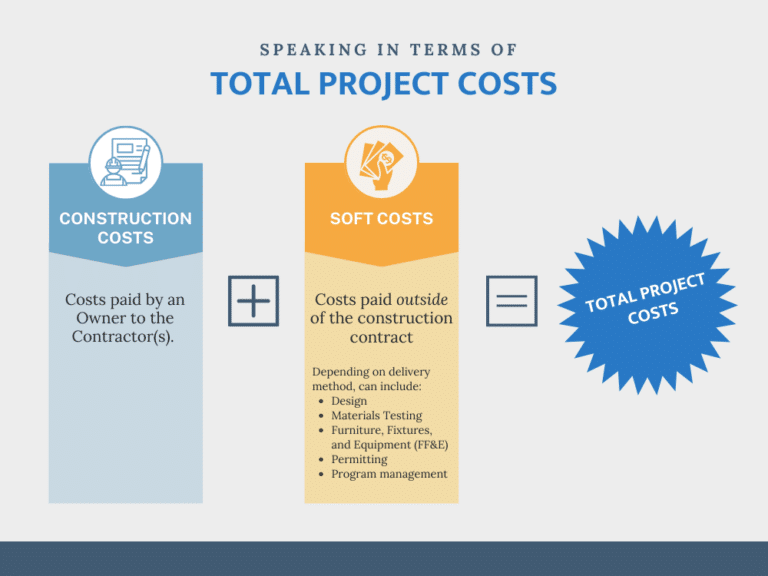

Closely related to consistent communication is the need to think and communicate in terms of Total Project Costs. Owners of construction projects have to understand the concepts of “construction costs,” “soft costs,” and “Total Project Costs.”

Construction costs are costs paid by an Owner to the Contractor(s). Soft costs are those costs that an Owner will pay outside of the construction contract. Depending on the delivery method, these can include items such as design, materials testing, Furniture, Fixtures, and Equipment (FF&E), permitting, program management, and other similar items.

Total Project Cost is the summation of the two (construction costs plus soft costs). In any economy, but particularly in one of extreme pricing volatility, it is important to consistently communicate in terms of Total Project Costs. It is never pleasant for Owners to focus only on the projected construction costs, only to learn that there could be an additional 15% to 30% in soft costs that they will have to spend to produce a functional facility.

One last point about Total Project Costs: as Owners and their Representatives consider Total Project Costs, it is also helpful to consider the projected benefits to be gained through the completion of the project. Considering both Total Project Costs and Total Benefits will give Owners and Owner Representatives a better understanding of the Total Value associated with a project.

Best Practice #5: Consider Current and Future Lifecycle Costs and Operational Costs

When establishing budgets, it is helpful to consider what impacts the construction of a facility might have on the current and future Lifecycle Costs (those costs associated with maintaining, repairing, and/or replacing building components) and and Operational Costs (such as utilities, staffing, transportation, etc.). In times of construction pricing volatility, keeping in mind the overall financial impact of a project to a system’s budget will aid advisors and decision makers in arriving at the right budget for a particular project.

Best Practice #6: Evaluate the Cost of Doing Nothing or Delaying Action

It is certainly understandable that some decision makers, when faced with rising and volatile prices, may want to delay or even cancel a project. And, at times, this may be the right decision. Regardless, when formulating and presenting budgets in a volatile economy – when projected numbers are likely higher than anyone expects or wants – it is helpful to be armed with an idea of the costs associated with delayed action or no action at all. High and volatile pricing projects may still be palatable to decision makers if the potential costs associated with delayed or no action are understood. This is one of the best examples of a “cost/benefit” or “risk/reward” conversation that an Owner’s Representative can have with an Owner.

Best Practice #7: Consider Multiple Sources of Information and Engage Independent Reviewers

When establishing project budgets, particularly early in a project, it is important to guard against “tunnel vision.” It is helpful to benchmark the projected costs of a facility against recent projects involving similar facilities. It can also be helpful to consider the projected costs per bed or projected costs per square foot (or whatever metric the team prefers).

Budgets should not be established looking at only one source of information, but instead should be established after carefully and critically considering all of the relevant information available to a team.

Best Practice #8: Identify Scope Variables

When establishing budgets, it is important to use neither the “best case” or the “worst case” scenario. Budgets should never assume the fattest scope (with the fattest budget) because the project would likely never get off the launch pad. Conversely, a project approved with the skinniest scope (and the skinniest budget) may have no chance succeeding when actual prices come in. The best practice is to establish a middle of the road scope and budget which allows for some growth in scope if actual pricing comes in better than projected, and which allows for some scope reduction if actual pricing comes in higher than projected.

Identifying those scope variables, and communicating them (and their corresponding costs and benefits) to decision makers during the budgeting process will better allow the entire team (Owner Representative, end users, and decision makers) to make better budgeting decisions at the beginning of a project. Keep in mind that a scope variable can be a question of both “what” and “when.” Rather than build the full scope at once, a phased project approach may be the best way to protect both scope and budget.

Best Practice #9: Consider Contingency Last

In times of volatile pricing, it’s easy for the first solution to be “increase contingency.” We would argue that this should be the last option considered. Certainly, every project Owner and their Representatives want to have a healthy contingency in the budget. But during the budgeting process, “beefing up” contingency should be considered after all of the preceding concepts have been considered and incorporated into the budgeting and planning process. If the first option to deal with pricing volatility is to increase contingency, this may end up being the only option considered.

Final Thoughts

Budgeting in today’s volatile economy is a challenging endeavor, to say the least. Owners can’t control the prices they receive during the procurement phase of a project. However, by taking a disciplined and methodical approach to establishing project budgets, Owners can give themselves the greatest chance of seeing a project through from planning and design to construction and operation.