Why the Need for Master Planning?

Planning – in its simplest form – can be defined as the process of devising and ordering steps to achieve a goal or outcome. While rarely “easy,” planning can be straightforward when certain things – one’s current state, available resources, applicable limitations, and desired future outcome – are known. When one or more of these items are not fully known, planning can become a much more intensive process.

Anyone familiar with the world of criminal justice would agree that it is constantly evolving and the items that are not fully known seem to be ever increasing. Planning for criminal justice systems and facilities is an intense process involving many stakeholders, the gathering and analysis of copious amounts of data, and the inevitable ‘cost-benefit’ tradeoff discussions between stakeholders. Further complicating matters is the reality that not all stakeholders will necessarily agree on the desired outcomes.

In late 2014, the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections was operating at 137% of capacity and did not have adequate space to meet the rehabilitation goals of the system. A comprehensive master plan was undertaken to provide a basis for meeting eight “Vision Goals” articulated by the Department.

Planning for criminal justice systems and facilities, if done properly, is an intensive effort that takes on a unique name – “Master Planning.” One could substitute the word “Comprehensive” for “Master” because the planning effort in question should strive to evaluate and consider all aspects of a criminal justice system or facility – factors such as facilities, operations, staffing, logistics, etc. As any correctional professional will attest, these factors are interrelated. A system’s staffing levels will affect its operations and logistics. A system’s facilities will affect its operations and logistics. These factors are not discrete. Master Planning efforts recognize and incorporate the interrelated aspect of each of these factors.

Three Key Components of Master Planning

To be done properly, Master Planning for criminal justice systems and facilities must involve the following key components:

1. Evaluation of Current Conditions / Projection of Future Conditions:

Honest evaluations of an organization’s current situation or conditions, and a data-based projection of future conditions, is a necessary first step in effective Master Planning. It is always a good investment of a planning team’s time to get as accurate a picture as possible of “where we are” currently and “where we think we are headed.” In the world of criminal justice master planning, this can include looking at some or all of the following:

- Current inmate population and classification

CGL was contracted to develop a facilities master plan for the Illinois Department of Correction (IDOC). The goal of this project was to prioritize and identify IDOC’s physical plant needs that would allow it to more effectively meet its mission and goals. As part of this work the CGL team conducted an existing conditions assessment of each correctional facility included in the study, identified individual facility practices, and prioritized overall system needs.

- Projected future inmate population and classification

- Facility Condition Assessment(s)

- Current successes and challenges and the root cause of each

- Current sentencing and parole trends

- Projected future sentencing and parole trends

- Current levels of violence and presence of contraband

- Current ratios of beds in cells vs. beds in dorms

- Current operational and supervision methodologies (i.e., direct supervision, indirect supervision, etc.)

- Current deferred maintenance costs

- Current and projected future recidivism levels

2. Evaluation of Available Resources and Applicable Limitations:

Experienced planners know that the plans they produce need to be achievable. It does no good to formulate a plan that can’t be executed. Evaluating available resources and applicable limitations, including reasonable assumptions about the future of each, will prevent planning teams from wasting time on courses of action that may look good on paper, but realistically can’t be achieved. As is said about some plans in the military, “it briefs well.” This means that a plan may look good on paper or on powerpoint, but in reality, it has little or no chance of success.

Examples of resources and limitations include (but certainly are not limited to) the following:

- Current and projected future staffing levels

- Current and projected future budgets

- Current and projected future inmate training programs

- Excess capacity within a system / availability of “swing space”

- Applicable laws and litigation settlement agreements

- Applicable industry standards and codes – ACA, ADA, PREA, etc.

- Political considerations (which, depending on the situation, could be either a resource or a limitation)

3. Documentation of Desired Outcomes:

Planning involves more than understanding one’s situation, resources, and limitations. The objective of planning – as the name implies – is to develop a plan to achieve one or more outcomes. Some of the outcomes commonly identified during planning processes are:

- Better protect public safety

- Provide better services for inmates

- Reduce recidivism by better preparing inmates for re-entry into society

- Modernize facilities to be “state of the art”

- Improve staff retention and wellness

- Reduce staffing requirements

- Improve operational efficiency / lower operational costs

Determining desired outcomes should not be purely qualitative, but instead should be influenced by data, if not driven by data. For example, if a national benchmark for a ratio of beds in cells to beds in dorms is 60-40 (celled beds to dorm beds), and a system’s overall ratio is significantly below that, then one goal of master planning could be to build and renovate facilities so that the system’s ratio more closely reflects the national benchmark.

Challenges of Master Planning

One of the challenges of Master Planning is that not all stakeholders and decision makers will necessarily agree on the desired outcomes. Some may say that their goal is to provide the highest level of public safety (by building secure facilities and keeping people incarcerated for long periods of time). Others may say that their goal is to minimize operational costs, which may mean fewer people incarcerated for shorter periods of time. One of the objectives of Master Planning is to identify desired outcomes, prioritize them, and then develop steps to achieve as many of the outcomes as possible.

One of the challenges of Master Planning is that not all stakeholders and decision makers will necessarily agree on the desired outcomes. Some may say that their goal is to provide the highest level of public safety (by building secure facilities and keeping people incarcerated for long periods of time). Others may say that their goal is to minimize operational costs, which may mean fewer people incarcerated for shorter periods of time. One of the objectives of Master Planning is to identify desired outcomes, prioritize them, and then develop steps to achieve as many of the outcomes as possible.

We are all familiar with the old adage, “when you try to please everyone, you end up pleasing no one.” The goal of Master Planning is not to ‘give everyone what they want’ because this is impossible. A more realistic goal of Master Planning is to identify desired outcomes and then align stakeholders toward achieving as many of those outcomes in the optimal manner for the organization.

The product or “deliverable” of a Master Planning effort is much more than simply a set of steps to achieve an outcome. Supreme Allied Commander and 34th President of the United States, Dwight David Eisenhower, said this about planning: “Plans are nothing. Planning is everything.” The real value of planning is not in the plan that is produced, but rather in the thought process that an organization goes through in developing the plan. Certainly Master Plans have value. But, as any military veteran will attest, no plan survives first contact. When (not if) a plan changes, the organization that has carefully evaluated current and future conditions, resources, and limitations will have the best chance of weathering change and achieving the long-term strategic outcomes outlined in the Master Plan.

Four Characteristics of Effective Master Plans

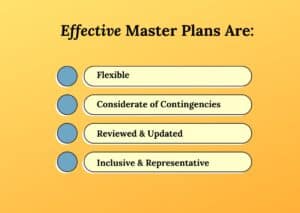

In addition to equipping an organization with the ability to achieve desired outcomes, in order to address the challenges described above, effective Master Plans (and Master Planning processes) should be:

1. Flexible:

As I mentioned previously, no plan survives first contact. Situations, conditions, and the corresponding plans will change. Effective Master Plans will not be rigid but instead will contain the flexibility to allow an organization to change and still achieve the desired outcomes. Yogi Berra once said, “When you come to a fork in the road… take it.” An effective Master Plan will allow an organization to take the inevitable forks in the road and still arrive at the desired destination.

2. Considerate of Contingencies:

During the Master Planning process, it is helpful to occasionally have the “what if” conversations:

- “What happens if this assumption does not prove to be true?”

- “What happens if the cost of a particular facility comes in much higher than expected?”

- “What happens if laws change and we have a different quantity of inmates with classification levels that differ from our projections?”

Talking through these contingencies, and others, during the planning process will prove invaluable to an organization during the implementation of the plan.

3. Reviewed and Updated Periodically:

A Master Plan should not be a document that is written, read once, and then put on the shelf, never to be reviewed again as the organization falls back to the status quo. To borrow a military term, a Master Plan should not be a ‘fire and forget’ weapon system. Instead, plans should be periodically reviewed and adjusted as needed to reflect actual developments that the organization experiences.

4. Inclusive and Representative:

As plans are developed, it is best practice to involve those people who will be responsible for implementing the plan. Having context and understanding “why” certain decisions were made during planning will prove invaluable during the implementation phase, when the inevitable challenges and changes arise and must be dealt with.

Planning, like many other things in life, involves a mixture of art and science. When done properly, the Master Planning process will be a challenge well worth the effort and equip justice leaders and facility administrators with the actionable insights required to make worthwhile change in their facilities and the justice system as a whole.

Download the PDF

This PDF is a valuable resource for all things Master Planning.