In 2011, for the first time in the history of our country, all of America’s state correctional directors met in Washington D.C. for three days to discuss and debate their role in this country’s criminal justice system. This meeting was convened by the Association of State Correctional Administrators (known today as the Correctional Leaders Association) and the Council of State Governments.

While discussions with this group were stimulated by experts like Dr. Ed Latessa, then director of the University of Cincinnati Corrections Institute, the real energy of this meeting came from robust debate among the correctional leaders themselves regarding an age-old question they were all too familiar with – “How could they positively and tangibly influence a criminal justice system that few respected?”

The Great Consensus – Three Key Outcomes

The greatest takeaway from that historic gathering? Correctional leaders from every state left the meetings with a consensus commitment to restore lives compared to the role of incapacitation once required during the period of prison growth; and as part of that commitment, all leaders in attendance agreed on the three important outcomes below:

- There are evidenced-based programs that can be delivered inside prisons that have been demonstrated to have positive influence on reducing future criminal activity, particularly if there is continuity into the community.

- A significant part of the responsibility of prison systems, and therefore its leaders, is to restore the lives of those confined and reduce the number that return to incarceration.

- In order to measure the impact of the efforts of leaders to reduce the return to prison for those incarcerated, the leaders agreed to utilize the first uniform definition of recidivism; “return to prison within three years of release”. Further, there was agreement to publish state results.

The three-day meeting ended with a new sense of purpose, a collaborative spirit and an understanding of how significant the leaders can be in promoting safer communities. These leaders, however, then left Washington and returned to their systems with physical plant designs and corresponding operational practices that challenged their new vision for their agency’s future. How would they achieve their restorative goals when faced with such daunting obstacles?

Tackling the Obstacles to Restorative Justice

To build, to renovate, to create operational change… or some of each?

While each system experiences individualized challenges, there are some common obstacles that correctional agencies face in meeting today’s expectations in yesterday’s facilities. I’ve outlined five of the most common obstacles below. The following points are designed to help a system or agency in determining how to create a restorative environment aligned with a vision of reducing future crime for those under custody given their physical plant limitations:

Obstacle 1: Lack of a Compelling Vision/Mission Statement

The most effective Mission and Vision statements are inclusive of all members of the organization, inspires and motivates positive change, and clearly communicates the core values that anchor the system.

Vision and mission statements were not intended to be written at some gathering of executive staff, published in a glossy book, and placed in a prominent place on a bookshelf only to be ignored on a daily basis. Quite the opposite – these statements should become a daily reminder and guide to what your agency aspires to be and the values that anchor who you are and what you do. Any focus on considering changes to the physical plant or operations should start with true and meaningful vision and mission statements. Some important considerations in developing these guiding principles include:

- Include ALL elements of the organization in the process. To be successful, you will depend on security, maintenance, healthcare, program staff, food service, office support staff, etc. Staff that feel included in the process will be more committed to supporting the agency and its successful future.

- Vision statements should INSPIRE. The whole purpose of a vision statement is to give people something to aspire to. Vision statements must inspire the agency, its staff and those under custody to move beyond its current place to a “better” place.

- Mission statements should identify CORE VALUES that will anchor daily operations. What are the values that will anchor your agency’s operations on a daily basis and promote staff behavior, treatment of those in custody and the agency’s role in creating healthy communities? These values should be clearly communicated in your mission statement.

An interesting approach to designing an agency future is underway in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice by Executive Director Bryan Collier. He challenged all the departments in the agency to imagine the agency in the year 2030 and tasked them with creating aspirational, yet achievable, goal statements for each operational and program area describing their area of responsibility in the year of 2030. As Director, Bryan has challenged staff to truly be creative in achieving a new system aligned with an aspiring vision statement.

Obstacle 2: Lack of Data Related to Physical Space

There are several important data points to measure when considering physical plant or operational changes.

The guiding principle that I utilize when undertaking initiatives is, “Data Driven; People Focused.” If we do not measure important performance metrics, not only do we not know our current state, but we will never know the progress we are making. Some examples of important data linked to consideration of physical plant or operational changes include:

- Population trends, projections, and profiles of the incarcerated – including security levels, gender, age, health and mental health diagnosis, recidivism and other reentry information

- Tracking restrictive housing numbers – Placing an individual in restrictive housing is a significant act given the potential negative impact it can produce and also because it is a leading source of litigation in our country today. Further, more negative incidents per capita take place in this setting than any other. A system should be able to know the number in restrictive housing at any time, in any facility including those on the mental health case load and how those numbers are trending. The effort to reduce restrictive housing should keep in mind that restrictive housing is not a housing unit, it is a condition of confinement that restricts an individual to a cell for 22 hours a day or more. So, with support from treatment and program staff, removing an individual from their cell for structured and unstructured programs and activities can substantially reduce numbers without changing units.

- Staffing and recruitment data – Recruiting and retaining correctional staff is the number one challenge facing correctional leaders today, as recognized by the Correctional leaders Association in its January 2023 meeting. Strategies to address this issue, particularly retention, must start with data, including vacancies, turnover by job classification by facility, by age and gender and by length of service; and for recruitment – length of time from application to being on payroll and most utilized sources used by applicants. Specific data from agencies will identify strategies that will work for that system and may not be responsive in another. For example, if many candidates are selected but do not show up for their first day, then the length of the hiring period may be a process to examine. If new staff are separating a short time after their training has ended, supervision may be an important element to challenge.

- Comprehensive reporting of incident data by facility – including type of incident, location, time of day, day of week.

- Program data including education, substance-use programming, mental health programming, and cognitive programming (e.g., “Thinking for a Change”). – This data should include those enrolled, those on waiting lists, physical capacities for programs and whether programs are delivered in central program areas or are residentially delivered in the housing units; as well as the number of staff assigned to these programs.

- Number of incarcerated people in need of critical care clinics – such as cancer, dialysis, diabetes, cardiac, dementia care – and the availability of those specialty care facilities in current facilities. Our strategic planning must think beyond today. As our populations in our prisons age and the aging process takes its toll medically and in terms of mental health on those incarcerated, what staff and physical design features will be necessary in five and ten years into the future?

Many systems realize they are housing individuals in an open setting that should be housed in an area where there is greater control.

Obstacle 3: Outdated Population Housing Design

Many facilities were built during times of massive prison growth, primarily for those convicted of drug offenses where the primary objective for construction was creating the most beds as efficiently and cost effectively as possible. As a result, housing units were often large and open dormitory settings suitable for warehousing the influx of population. In recent years – consistent with the theme of reducing recidivism coming from the 2011 All Directors meeting – the diversion of non-violent, often addicted individuals to community settings more effective with this population accelerated in most states.

This has left prison populations with a greater density of more violent individuals not suitable for the existing style of housing. A security assessment of the system’s population compared to the size and type of housing [e.g. dormitory, cells] is critical to ensure safe environments for both staff and those incarcerated. This assessment needs to take into consideration current trends and pending legislation that may impact sentencing.

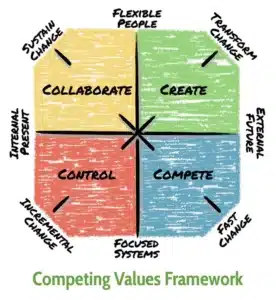

The Organizational Cultural Assessment Instrument (OCAI) is a psychometric tool developed by Kim Cameron and Robert Quinn to help organizations identify their current and preferred culture.

Obstacle 4: Unhealthy Staff Culture

Our profession is a people business; and regardless of how talented leadership may be, facilities operate through the execution of duties and services by all members of the workforce. If staff do not enjoy coming to work and do not see the value of their labor, they will not perform well. Simply put, if staff culture is not healthy, the initiatives of an agency or facility leader will not be sustained.

So how do you begin to address unhealthy culture? Like any important initiative, it’s important to start with an accurate idea of where you currently stand. Performing a culture assessment of your facility or agency is a great place to start.

Culture in jails and prisons can be assessed through a qualitative and quantitative process based on the OCAI work from the 1980s and adapted to correctional environments by a diverse team assembled by the National Institute of Corrections. The assessment is designed to lead to a strategic approach to improve facility culture.

Final Thoughts

As correctional leaders, we have a limited time to make a real difference in the lives of our staff, those we incarcerate, and ultimately in our communities. At the same time, there are clearly obstacles that, when left unaddressed, have the tendency to encourage the continuation of the current state. As with any obstacle we face in life, the first step to addressing the problem is being aware that it exists in the first place, and to what extent. From there, it’s up to us as leaders to seek the right strategies and tools to help us get to the future we envisioned, and agreed upon, over those three days of meetings in D.C.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

If you’re interested in learning more, check out our 360 Justice Podcast where I share my thoughts on the future of rehabilitation and corrections: Analyzing the Future of Rehabilitation with Former ACA President, Gary Mohr